Wherefore go-saturate

In my previous blog post, I wrote about a bottleneck I ran into that caused my application to pause when I felt it should’ve been working hard.

My workers were all stuck waiting for data from one source while other sources of the same data were available.

This is how I fixed it.

Problems Illustrated

First, it’s good to see exactly what the problem looked like.

There are four workers and they all need a mix of data of type a or

b. Both a and b data sets are replicated so any given record

can come from one of two of these servers.

If there are equal tasks for a and b and servers are all generally

available, but one of the servers is slower than the others, then you

will invariably end up with all of the workers stuck retrieving data

from a rep 1 even though a rep 2 contains the same data.

But why is it blocked on that node? Because that node is slow.

When randomly selecting workers and one worker takes considerably longer to complete its work, you will inevitably be blocked waiting for slower workers to complete their tasks.

If this isn’t intuitive to you, think about it this way:

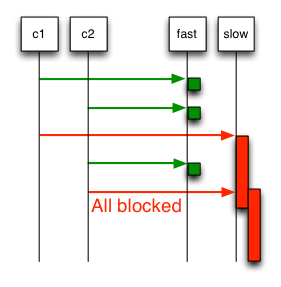

Imagine just two servers containing the same information from which you randomly choose for any given request. Let’s say one server is 8x slower than the other.

Assume a reasonable random number generator such that there’s a 50% chance that any given request will be issued against the fast one, and a 50% chance it will be issued against the slow one.

Now imagine you’ve got two clients that are wanting to grab a bunch of data from the two servers.

The scenario illustrated above will occur frequently:

- Client 1 hits the fast server.

- Client 2 hits the fast server.

- Client 1 hits the slow server - is blocked for a while.

- Client 2 hits the fast server again.

- Client 2 hits the slow server - all workers are blocked while the fast server is idle.

Boo.

What Does go-saturate Do About This?

If you can express your work in the form of (task, []resources)

pairs, you can use go-saturate to help resolve this

type of problem with a double-fanout as illustrated and discussed

below.

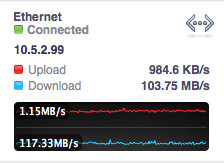

Internally, the resources are each represented by a channel that has one or more goroutines servicing it (user-specified). A resource is “available” when a worker is idle and just waiting for new work on a channel. If the resource is slow, the worker spends more time working and less time accepting new work (see the red in the sequence diagram above).

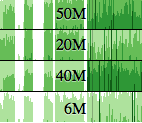

The diagram to the right represents a producer feeding into two tiers

of workers. The first tier workers, e.g. worker 1 are higher level

(e.g. copy a file from the internet to local disk) while the second

tier workers, e.g. a rep 1 are lower-level (e.g. read this file from

this location).

It’s important to understand that the first-tier workers are in the same process as the second tier workers, the distinction being that the second tier workers are operating on a resource identified by the first tier workers and the duration of that work isn’t necessarily predictable.

In the illustrated case, workers 1 and 3 are concurrently performing

tasks that need data from a.

Let’s break down the specific example shown in that diagram.

- The producer submits two tasks that both need information from

a - Workers 1 and 3 pick up this work.

- They both identify

a rep 1anda rep 2workers as being possible sources ofa. - The

selectfrom worker 1 choosesa rep 2 - The

selectfrom worker 3 choosesa rep 1

Note that steps 4 and 5 can occur at approximately the same time, but

the a rep 1 worker can only pick up one job and the first-tier

worker (e.g. worker 1) can only have one worker pick up its task.

By asking for one of either and choosing the most available resource,

they’re able to do their work without blocking on each other. For

example, if a rep 1 is slow, tasks requiring a will continue to

get their as from a rep 2 as fast as that replica can keep up.

In a sense, the resources are self-selecting.

Here is a concrete example that illustrates go-saturate in the real world. It’s being used in the cbfs client code. (cbfs is a distributed blob store for Couchbase Server).

As you can see in the right (a cbfs scenario where one server has 100Mbps ethernet and the others have gig-e), slow resources are still used, but when a slow resource is being slow and a fast resource is available, we won’t choose the slow one.

In long-running tasks, this is great – if I can keep all the fast nodes and the slow nodes busy, then I get a little more out of the network as a whole.

Other Resources

You can read the go-saturate docs to get an overview of the API.

Also, I gave a presentation at work earlier this week on this topic which goes a lot further into basic go channel semantics interactively including a range of information from basics like how to send and receive on a channel to how send a message to exactly one of a dynamically built set of recipients.

That presentation is captured in the following 20 minute video:

Both the slides and the long-form contents of the material used in that presentation are available.