SubTree - An MQTT Subscription Tree

I do a lot of iot junk and use mqtt quite a bit. Somehow I ended up writing my own mqtt broker in Haskell along the way. There was one core part of the server that I thought would be really hard, but ended up being one of my favorite pieces of code, though it’s only about 50 lines long. I wanted to describe why.

First, a bit of background.

MQTT

MQTT is basically a pubsub service for IoT like things. Little devices connect to an MQTT broker so other devices connected to the MQTT broker can pick up those messages via subscriptions. It’s a bit complicated and there are a lot of details, but I’ll try to simplify to the relevant points.

Publishing

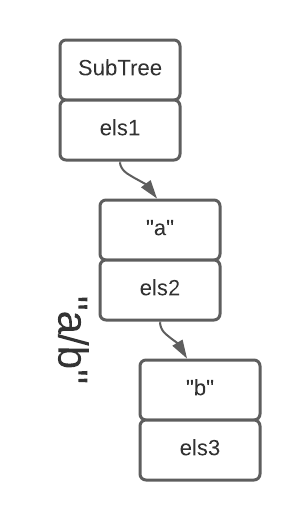

Messages are published to topics that are slash-separated strings,

e.g. a/b/c. The broker’s job is to decide who wants to receive

messages published to a/b/c and delivers a copy of the message to

that subscriber.

Subscribing

Multiple clients can subscribe to topics either specifically, e.g.,

a/b/c or by a couple different wildcards. + can replace any

single path element, e.g., +/b/c or a/+/c or +/+/+ or whatever.

# can appear as the last element in a path and matches anything

below the current path. Also: topics whose first character is $ are

not automatically matched by a toplevel #. i.e., $x/blah will not

be matched by # but it will be matched by $x/#.

The specific rules aren’t too important, but it’s complicated enough that you can’t just use a simple Map to locate subscribers and there may be multiple subscribers for every published topic.

Other Fancy Things

There’s also a concept of “shared subscriptions” that allows multiple subscribers to round robin messages and we need to be able to deal with unsubscribing or timing out clients and forgetting subscriptions, so we need to handle a couple other cases specially. These are all doable without excessive consideration of the data structure.

Interesting Type Classes

Setting aside the specific goals for a bit, let’s look into a few

type classes that we’d like our SubTree type to satisfy to make

things easier to think about.

Semigroup

A Semigroup at a high level just means you have an associative binary operation that is used to “combine” two things. This is a bit hand wavy, but if you think about it as set union or list concatenation, you’re on the right track for most of the purposes here.

I wanted my SubTree to be a semigroup such that a <> b does

whatever you might think of as a natural combination of two

SubTrees. SubTree itself is * -> *, so it’s parameterized on a

type. A Semigroup of SubTree a is only meaningful when a

itself is a Semigroup. i.e., if you have a SubTree [Int] then

combining two SubTree values would produce a new SubTree with all

of the same subscribers for all of the topics from both values.

Monoid

A Monoid is basically just a Semigroup with an “identity”

value. The “identity” value can be combined to either end via the

semigroup <> operator and you’ll end up with the same value. e.g.,

"a" <> "" == "a" and "" <> "a" == "a".

Similarly to Semigroup, when I have a SubTree a and a is a

Monoid, I wanted SubTree a to also be a Monoid, making mempty

do the right thing for constructing an empty SubTree.

This doesn’t look like much so far, but it gets more powerful as we go.

Functor

Since my SubTree is parameterized and conceptually a container, it

makes a lot of sense to have it be a Functor.

A Functor gives you a way to take a SubTree a and convert it to a

SubTree b if you have a function (a -> b). One way to think of

this is to imagine your function f :: a -> b being placed in front

of every a in the SubTree a which naturally makes every a into a

b.

e.g., if I have a SubTree [String] where I map subscription filters

to a list of strings and I want to have a SubTree Int where I map

filters to the number of subscribers, then that’s just fmap length

and we’re done.

The laws require the “shape” of the structure not change while

performing such a transformation. Mapping a list over a function

gives you a new list with the same number of elements. Simiarly,

mapping a SubTree over a function gives you the same subscription

structure, but changes only the values.

Foldable

Foldable is an abstraction for doing stuff to all of the

elements of a container. It gives you such great bits as foldr and

fold and toList. Where Functor gives you a shape-preserving

mechanism to operate across a value, Foldable provides catamorphisms

allowing you to reduce a value to a structure of a different shape.

For example, if you want to know how many subscribers are found within

a SubTree [String] named t you can write something like foldMap (Sum

. length) t and your Foldable implementation and the Sum Monoid

does the rest of the work for you.

Traversable

Traversable is a bit of a fancier Functor that allows

for effects and a few other things that aren’t necessarily interesting

for this discussion, but when you’re building a container, it’s good

to have around.

Finally, the SubTree Type

So now that we’ve covered all of the desirable properties, the

long-dreaded SubTree ended up being mostly just this:

data SubTree a = SubTree {

subs :: Maybe a

, children :: Map Filter (SubTree a)

} deriving (Show, Eq, Functor, Foldable, Traversable)

It’s a tree that may have subscribers at any given level, and it may

have children below it. I think I hand-wrote Functor et. al. before

just trusting the compiler to do the right thing (there should be only

one valid implementation, anyway). So at this point, we’re almost

done with most normal storage bits.

Semigroup and Monoid require a bit more more work, so let’s

implement those really quickly before we move on:

instance Semigroup a => Semigroup (SubTree a) where

a <> b = SubTree (subs a <> subs b) (Map.unionWith (<>) (children a) (children b))

empty :: SubTree a

empty = SubTree Nothing mempty

instance Monoid a => Monoid (SubTree a) where

mempty = empty

(note that empty exists so we can have non-monoidal empty

SubTrees)

Modification

In order to add, change, or remove subscriptions in a SubTree, we

introduce the modify function. It’s the most general mechanism for

performing any modifications, so it gets a pretty generic name. It

looks like this:

modify :: Filter -> (Maybe a -> Maybe a) -> SubTree a -> SubTree a

i.e., for a given Filter and a function that takes a maybe-existing

value and returns a new maybe-existing value, we can do our thing.

The actual implementation leverages Data.Map’s alter function

which does most of the work here, but the actual implementation is

just a couple of lines:

modify :: Filter -> (Maybe a -> Maybe a) -> SubTree a -> SubTree a

modify top f = go (splitOn "/" top)

where

go [] n@SubTree{..} = n{subs=f subs}

go (x:xs) n@SubTree{..} = n{children=Map.alter (fmap (go xs) . maybe (Just empty) Just) x children}

We start by splitting the filter topic on / so we have the segments

and then we walk the tree. If the remaining topic is [] then we’ve

arrived at the topic we’re looking for and we just run the

transformation function and we’re done. Otherwise, we walk the tree

using alter which will create any necessary subtrees as we go.

Note that this would be slightly simpler if we required a to be

monoidal, but fewer constraints are possible, so we did the broadest

thing here.

It’s a little awkward to use, though, so we also have addWith:

addWith :: Monoid a => Filter -> (a -> a -> a) -> a -> SubTree a -> SubTree a

addWith top f i = modify top (fmap (f i) . maybe (Just mempty) Just)

addWith assumes a is monoidal and gives us a far simpler

transformation by just allowing us to add a specific value with a

collision function to deal with existing cases.

e.g., the most simple case, add:

add :: Monoid a => Filter -> a -> SubTree a -> SubTree a

add top = addWith top (<>)

add does the thing you’d expect when adding a new value. e.g., if

you have a SubTree [Int] that has subscribers at a/b/c of [1,2]

and you add [3] at that path, you’ll have [1,2,3].

This is also how we build fromList:

fromList :: Monoid a => [(Filter, a)] -> SubTree a

fromList = foldr (uncurry add) mempty

Searching

And now, the entire reason this thing exists: finding subscribers.

The most general function we have for this is findMap which has a

fairly simple signature:

findMap :: Monoid m => Topic -> (a -> m) -> SubTree a -> m

I’m going to omit all the code here since it’s about 8 lines long

because of all the weird expansion rules, but the signature tells us

really everything we need to know. It looks a lot like foldMap.

Given a topic and a function that converts whatever a is found for

that topic to a monoidal value, you get a monoidal value.

e.g., if the a is already a monoid, you get this function:

find :: Monoid a => Topic -> SubTree a -> a

find top = findMap top id

So when I store my subscriptions as a list, find "some/topic" st

gives me a list of all the things subscribed as some/topic or

+/topic or topic/+ or topic/# or #.

In Practice

In my original implementation of my mqtt broker, I implemented subscriptions as a dumb list. It seemed like it was going to be a hard problem, so I punted until I could do something better. Every message that was published had to look at every subscription for every client and see which ones matched before redistributing stuff. For my little server at home, I have around 250 subsriptions at any point in time and get about one message per second on average. That’s on the verge of gross.

But it turned out to be very easy to implement something efficient

that worked quite well. I just have a TVar that holds a

SubTree (Map SessionID SubOptions) and just use stm to do the

reads and writes. The semantics are still quite complicated as

there are private and shared subscriptions and there’s the session

vs. client separation and being able to have concurrent deliveries of

messages sent by one client to any relevant subscribers while new

clients are concurrently modifying the subscription SubTree.

Being able to express data structures like this and test them thoroughly against well-established laws makes me avoid having to think of large swaths of bugs I’d write in most other languages.

I replaced mosquitto with my own mqttd project a year or so ago due to a couple strange bugs I’d encounter occasionally and some missing features of MQTT v5 I wanted to use. I’m around 1,400 lines in with a solid broker I’m relying on.

But SubTree.hs is one of my favorite pieces of code.